Ways of life 2: Another perspective

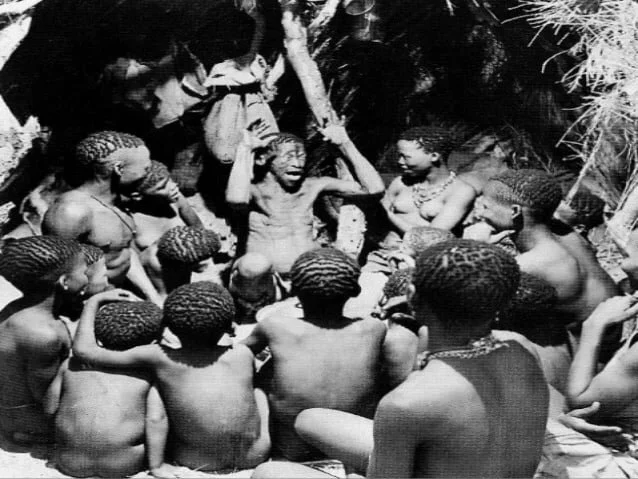

Khoi San of Southern Africa

Originally published by This Is Africa, January 11, 2016

Editor’s note: This article is the second in a three-part series investigating different ways of organising human life on earth. The first installment is here.

In recent times there have been many articles such as Europeans did NOT bring shoes to Africa, The forgotten masterpieces of African modernism, and 11 Ancient African Writing Systems That Demolish the Myth that Black People were Illiterate. On one level efforts that dispel myths of the under-development of African civilisations should of course be applauded. But on another level these attempts at proving that African peoples are just as advanced as Europeans is based on a Eurocentric definition of advancement, rely on a set of modern-centric criteria and measurements of achievement, and missing a crucially important point: older cultures in Africa and all over the planet developed in fundamentally different ways, formed different world views, with different concepts and different methods, than capitalist modernity. Here I will briefly demonstrate, with only a few examples, taken from the 3 articles cited above, how the ways of life developed by ancestral cultures are not only different, but often, objectively speaking, much more sophisticated and advanced than ours, but in their own way, not always in ours.

Pre-modern and non-Western cultures must be evaluated in their own context, on their own terms, according to their own criteria, and can not be judged according to “civilised” and modern standards, in congruence with Western definition of “progress”.

Shoes

“If you offer people that live in rain forests shoes, they would be puzzled: ‘Why would I want to wear these things which make my feet sweat, keep me from feeling the ground, and detach me from intimate knowledge of the earth?”

Nomads in the Sahara possess almost supernatural comprehension of the desert. It is said , once they have seen a single plant in the middle of endless and constantly shifting sand dunes (indication of underground water), they can find the exact location again a year later. Traditional healers in Namibia have cultivated incredibly rich ethno-pharmacological knowledge of medicinal plants and their uses which multinational pharmaceutical corporations can not wait to exploit. In the Americas, native Alaskans developed methods for determining where to build trails in anticipation of whaling season by watching the formation of ice for months in advance. In such enumerable cases, detailed and complex understanding of the environment, including climatic patterns, plant species, and animal behavior, informs the organization of human society, creating holistic living systems in which everything is inextricably connected.

Photo: ngomasound.com

“Pre-civilized” cultures often employ methods which todays’ science struggles and fails to understand. For instance, there are myriad ways in which the Aguaruna people of the Amazonas in Peru (who also refuse to wear shoes) and other indigenous groups use combinations of plants, often prepared by elaborate processes, that modern medicine can not explain. The synthesis of many different species to unlock their profoundly powerful effects, for the specific purposes of healing and spiritual awakening, known as Ayahuasca, is one such process. Botanists and biologists have no idea how this knowledge was arrived at: shamans maintain that it is from guidance of the plants themselves.

Indeed, groups such as the Aguaruna have not only deep knowledge of nature, but ways of knowing which are lost to city dwellers. Over millennia, peoples in the rain forests built vast bodies of knowledge about their incredibly ecologically diverse environment, which they have recently compiled into an Encyclopedia of Traditional Medicine.

Architecture

Dwellings made of bio-degradable materials which disappear back into the jungle after 1 or 2 seasons are not necessarily any more “primitive” than buildings made of stone or steel. They are actually, in ways we are only beginning to once again understand, with the relatively recent discourse on sustainability, more efficient, effective, and intelligent. A temporary shelter made of branches, vines, and leaves might take only some days or even hours to construct, yet keeps the occupants shielded from danger and rain, warm at night, cool during the day, serving their every need. At the same time, the process produces no waste and leaves no ecological foot prints. Similar to this type of structures in Africa, native peoples everywhere have figured out brilliant architectural solutions which provide optimum conditions while being in balance with the eco-system, sometimes completely baffling modern architects with their ingenuity.

Photo: ngomasound.com

The use of fractals and self-organizing patterns in the architecture and design of many cultures in Africa – ideas and methods not “invented” in the West until the 1970s – has been a topic of study for mathematician Ron Eglash. Strategic applications of these sophisticated algorithms are found all over, and are unique to, the continent of Africa, with geometric patterns often matching the organizational patterns of societies. From culture to culture, fractal structures are used in different ways, but are a common design practice and widely “shared technology”. For instance, non-linear scaling fences in the Sahel regions, very different from fences outside of Africa, take into account the relationship between height from the ground and wind speed; the fence gets gradually thicker as they get higher according to a fractal algorithm.

“When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganized and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t yet discovered,” said Ron Eglash.

And the only reason things like this are impressive to us now, from the modern perspective, is because in these cases science has eventually caught up with the advancement of the old ways.

Language

The diverse oral traditions which have sustained and enriched indigenous people in Africa and elsewhere for countless millennia are far from being any less accurate, broad, vast, varied, or nuanced than any written literary tradition, in fact, they are much more so. The written word until recently had always been an elitist technology guarded by the literate aristocracy, and favoured centralized, hierarchical, and one-way communication. Printing further institutionalized the problem. Versions of history of the rich and powerful – who controlled the printing presses – which almost invariably did not reflect the perspectives of the people, were disseminated as objective truth. But in oral traditions, egalitarian social fabric sown together by the intimate passing of verifiable first-hand knowledge protects communities from pandemic lies and propaganda. The incredible accuracy of verbal accounts have been proven time and again. There are Australian aborigines who convey specific geographic information about ancient floods which took place many tens of thousands of years ago, facts only verified by geologists in the past few decades. Similarly, Native Americans, Polynesians, Sami people of Finland, and “pre-civilized” people everywhere have preserved amazingly detailed accounts of events stretching far back into history (the ones who care to).

In many places like Somalia, India, or regions in China where ethnic minorities still thrive, stories are often told in poetry form, sometimes sung, accompanied by gestures, rhythm, even elements of theater and dance. Use of language in these traditions is at once extremely compact, expansive, multi-layered, and powerfully expressive. The affinity of phonetic communication, with all of its complex dynamics of extra-lingual and non-verbal cues, engages the listener in a more actively participatory role. Face to face organic transmission of knowledge is able to have both psychological impact as well as cognitive depth, conveying meaning with both more immediacy and profundity. The free jazz musician William Parker once noted that recorded music is “canned music”; similarly, oral traditions transcribe living, multi-faceted images, stories, understanding, and insight, as opposed to reading impersonal information on a page, which more likely remains one-dimensional and superficial in the brain.

No, I am not suggesting that we should stop wearing shoes, live in handmade dwellings, and burn all books. But with these examples, I hope I have provided glimpses of another perspective which is largely missing today, suppressed by prevailing ideology. And I hope I have shown that in many ways it is the modern, globalized, and dominant value systems which are backwards and upside down. Besides Euro-centrism, which has had a pervasive influence on our understanding of ourselves and of the world, there is another, perhaps more harmful prejudice in which we may be even more entrenched: Modern-centrism. Our society endlessly describes the ways that technologies give, and completely ignore the ways that they at the same time take away. It is of critical importance, for the future of mankind, to examine with sober, objective eyes, both what we have gained as well as what we have lost, with the advent of things like shoes, permanent housing, and the written word.

Maybe what is needed now, if we are interested in solving the many urgent problems we face as a species, is a re-evaluation of the criteria of valuation: what should be on the list of things we value. “Pre-civilized” non-western cultures invested their energy in projects other than steel making and weapons engineering, and have sets of priorities and goals other than wealth accumulation or expansionism. From them we can learn lessons not only beneficial, but which just might save us from disaster.